This post belongs to the Three real-world examples of distributed Elixir series.

- A gentle introduction to distributed Elixir.

- The tale of the periodic singleton process and the three different global registries.

- The distributed download requester and progress tracker.

- The distributed application version monitor.

In the last part of the series, we saw how to create a singleton process across a cluster of nodes, using three different global registries. This approach is commonly used to run a unique background task that you want to keep running no matter what changes happen in the cluster’s topology. However, we can use a similar pattern to run short-time running tasks that will die once they finish their job, with the same guarantees. An excellent example of this would be an application where users can download a file. However, generating the file is an expensive task that can take some seconds, and you want to notify the user of the progress. Eventually, when the file is ready, the application should provide the user with the download URL. Of course, all these should happen if the node where the download task is running shuts down, the user refreshes the page connecting to a different instance, etc. Let’s get cracking!

The base application

For today’s example, we will create a web application on top of:

- libcluster for building the cluster of nodes.

- Horde to handle both the process registry and supervision, as we saw in the previous part of the series.

- Phoenix, Elixir’s web framework, designed and built from the ground up to take advantage of Elixir’s distribution features.

- Phoenix.LiveView for the front-end to give real-time updates to the user.

Let’s start by generating a new project from the terminal:

mix phx.new download_manager --no-ecto --live --no-dashboard --no-gettextNext, let’s add the initial dependencies that we need and configure the cluster definition:

# ./mix.exs

defmodule DownloadManager.MixProject do

use Mix.Project

# ...

defp deps do

[

# ...

{:libcluster, "~> 3.3"},

{:horde, "~> 0.8.3"},

]

end

# ...

end# .lib/download_manager/application.ex

defmodule DownloadManager.Application do

use Application

def start(_type, _args) do

children = [

{Cluster.Supervisor, [topologies(), [name: BackgroundJob.ClusterSupervisor]]},

# Start the Telemetry supervisor

DownloadManagerWeb.Telemetry,

# Start the PubSub system

{Phoenix.PubSub, name: DownloadManager.PubSub},

DownloadManager.HordeRegistry,

DownloadManager.HordeSupervisor,

DownloadManager.NodeObserver,

# Start the Endpoint (http/https)

DownloadManagerWeb.Endpoint

]

opts = [strategy: :one_for_one, name: DownloadManager.Supervisor]

Supervisor.start_link(children, opts)

end

def config_change(changed, _new, removed) do

DownloadManagerWeb.Endpoint.config_change(changed, removed)

:ok

end

defp topologies do

[

background_job: [

strategy: Cluster.Strategy.Gossip

]

]

end

end

We are not going to dive into the details of the DownloadManager.HordeRegistry, DownloadManager.HordeSupervisor, and DownloadManager.NodeObserver, since we already did in the last part. Still, they are the modules needed to make Horde work appropriately in a cluster of dynamic nodes, so we will just copy them and rename their namespace to match the current DownloadManager. Since we will start multiple nodes and Phoenix runs in port 4000 by default, we will have issues due to the port already taken by the first instance that we start. Let’s change the development configuration so that it takes the port number from the environment:

# ./config/dev.exs

use Mix.Config

config :download_manager, DownloadManagerWeb.Endpoint,

http: [

port: String.to_integer(System.get_env("PORT") || "4000")

],

# ...Last but not least, let’s get rid of all the predefined Phoenix styles and, to create a simple yet beautiful UI, let’s add the Tailwind CSS CDN stylesheet link:

# ./lib/download_manager_web/templates/layout/root.html.leex

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

# ...

<link href="https://unpkg.com/tailwindcss@^2/dist/tailwind.min.css" rel="stylesheet">

# ...

</head>

<body>

<%= @inner_content %>

</body>

</html>We are not going to do an in-depth exploration of the styles either. However, you can find all the files in the example repository, and this is how the final result looks like:

The downlad struct and repository

With the basic project structure ready, let’s start working on the download request logic. First of all, let’s define what a download request looks like:

# ./lib/download_manager/download.ex

defmodule DownloadManager.Download do

alias __MODULE__

alias DownloadManager.Token

@pending_state :pending

@processing_state :processing

@error_state :error

@ready_state :ready

@enforce_keys [:id, :state, :user_id]

defstruct [

:file_url,

:id,

:state,

:user_id

]

def new(params) do

with {:ok, user_id} <- Keyword.fetch(params, :user_id) do

%Download{

id: Token.generate(),

state: @pending_state,

user_id: user_id

}

end

end

end

The DownloadManager.Download struct holds the following data:

-

id: the unique internal ID of the download. -

state: the current state of the download, which can be any of:pending,:processing,:error, or:ready. -

file_url: the downloadable file’s URL. -

user_id: the ID of the user who requested the download.

We are also adding a convenient new/1 helper function to build download structs, which by default sets an randomly generated :id value along with the :pending state. In a real-life application, we would temporarily store download requests in some sort of in-memory data storage like the good old Redis. However, we will stick to our no-external-dependencies approach and define a new module that serves as the download request repository:

# ./lib/download_manager/download/repo.ex

defmodule DownloadManager.Download.Repo do

alias DownloadManager.Download

@adapter Application.compile_env(:download_manager, __MODULE__)[:adapter]

@type user_id :: String.t()

@type result :: {:ok, Download.t()} | {:error, term}

@callback start(keyword) :: GenServer.on_start()

@callback fetch(user_id()) :: result

@callback insert(Download.t()) :: result

@callback update(Download.t()) :: result

@callback remove(Download.t()) :: result

defdelegate start_link(opts), to: @adapter

defdelegate fetch(user_id), to: @adapter

defdelegate insert(download), to: @adapter

defdelegate update(download), to: @adapter

defdelegate remove(download), to: @adapter

def child_spec(opts) do

%{

id: __MODULE__,

start: {__MODULE__, :start_link, [opts]},

type: :worker,

restart: :permanent,

shutdown: 500

}

end

endThis module defines five different behavior callbacks:

-

start/1: which starts the current adapter. -

fetch/1: which searches the current download for a givenuser_id. -

insert/1: which inserts the given download. -

update/1: which updates the given download. -

remove/1: which deletes the given download.

Using dependency injection to set the @adapter module variable, it delegates all the public functions to the configured adapter. This technique is very convenient when you want to have different adapters for different environments, especially when the production adapter points to an external service, but you want your tests to use a mock implementation to avoid any external dependencies. For the sake simplicity, we will use nebulex, which is a distributed in-memory cache library, so let’s add it to the application dependencies:

# ./mix.exs

defmodule DownloadManager.MixProject do

use Mix.Project

# ...

defp deps do

[

# ...

# Additional deps

# ...

{:nebulex, "~> 2.1"}

]

end

# ...

end

Next, we can implement a DownloadManager.Download.Repo adapter module following nebulex’s documentation:

# .lib/download_manager/download/repo/nebulex.ex

defmodule DownloadManager.Download.Repo.Nebulex do

use Nebulex.Cache,

otp_app: :download_manager,

adapter: Nebulex.Adapters.Replicated

alias DownloadManager.{Download, Download.Repo}

@behaviour Repo

@impl Repo

def start(opts) do

start_link(opts)

end

@impl Repo

def fetch(user_id) do

case get(user_id) do

nil ->

{:error, :not_found}

download ->

{:ok, download}

end

end

@impl Repo

def insert(%Download{user_id: user_id} = download) do

if put_new(user_id, download) do

{:ok, download}

else

{:error, :unexpected_error}

end

end

@impl Repo

def update(%Download{user_id: user_id} = download) do

:ok = put(user_id, download, ttl: :timer.seconds(5))

{:ok, download}

end

@impl Repo

def remove(%Download{user_id: user_id} = download) do

:ok = delete(user_id)

{:ok, download}

end

end

The module implements the DownloadManager.Download.Repo behavior by calling the specific Nebulex functions in its callbacks, thanks to Nebulex’s convenient API. Finally, we have to configure the repository’s adapter in the application’s configuration, and add the repository module to the main application supervision tree:

# ./config/config.exs

use Mix.Config

# ...

config :download_manager, DownloadManager.Download.Repo,

adapter: DownloadManager.Download.Repo.Nebulex

# ...# .lib/download_manager/application.ex

defmodule DownloadManager.Application do

use Application

def start(_type, _args) do

children = [

# ...

DownloadManager.Download.Repo,

# ...

]

opts = [strategy: :one_for_one, name: DownloadManager.Supervisor]

Supervisor.start_link(children, opts)

end

# ...

endLet’s jump to the interactive shell and test out the repository:

➜ iex --sname n1 -S mix

# ...

iex(n1@mbp)1> [user_id: "user-1"] |> DownloadManager.Download.new() |> DownloadManager.Download.Repo.insert()

{:ok,

%DownloadManager.Download{

file_url: nil,

id: "sOB4hY6ylz",

state: :pending,

user_id: "user-1"

}}

If we start a different node and try to get the download for user-1, we should be able to see it:

➜ iex --sname n2 -S mix

# ...

iex(n2@mbp)1> DownloadManager.Download.Repo.fetch("user-1")

{:ok,

%DownloadManager.Download{

file_url: nil,

id: "XLaXS2YeOO",

state: :pending,

user_id: "user-1"

}}Creating and tracking downloads

With the download definition and the distributed repository working, we can move on to the next thing: requesting a download and tracking its progress. First, let’s implement the module which starts new download request processes:

# ./lib/download_manager/download/tracker.ex

defmodule DownloadManager.Download.Tracker do

alias __MODULE__.Worker

alias DownloadManager.{Download, Download.Repo, HordeRegistry, HordeSupervisor}

@spec start(String.t()) :: {:ok, Download.t()} | {:error, term}

def start(user_id) do

with download <- Download.new(user_id: user_id),

{:ok, download} <- Repo.insert(download),

child_spec <- worker_spec(download),

{:ok, _} <- HordeSupervisor.start_child(child_spec) do

{:ok, download}

end

end

defp worker_spec(%Download{user_id: user_id} = download) do

%{

id: {Worker, user_id},

start: {Worker, :start_link, [[download: download, name: via_tuple(user_id)]]},

type: :worker,

restart: :transient

}

end

defp via_tuple(id) do

{:via, Horde.Registry, {HordeRegistry, {Download, id}}}

end

end

The Tracker module exposes a public start function that expects a user_id. Using this ID generates a new download, inserts it into the repository, generates a worker child spec, and finally starts the tracker worker process using the Horde supervisor, returning the created download. Please notice the {:via, Horde.Registry, {HordeRegistry, {Download, id}}} name option it sets in the worker spec to register the process globally across all nodes. The worker’s responsibility is simple: to keep track of the download file generation reporting the progress. Nevertheless, depending on your particular case, generating downloadable files can imply different things, from processing significant amounts of data locally to relying on an external service, having to handle the communication between both applications. Therefore, let’s follow the same dependency injection approach that we took in the download repository and create a worker behavior module:

# ./lib/download_manager/download/tracker/worker.ex

defmodule DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.Worker do

@adapter Application.compile_env(:download_manager, __MODULE__)[:adapter]

@callback start_link(keyword) :: GenServer.on_start()

defdelegate start_link(opts), to: @adapter

endAgain, for the sake of simplicity, we are going to build a fake worker implementation that gives us enough time to mess around in the interactive shell:

# ./lib/download_manager/download/tracker/worker/fake.ex

defmodule DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.Worker.Fake do

use GenServer

alias DownloadManager.{Download, Download.Repo}

alias Phoenix.PubSub

def start_link(opts) do

name = Keyword.get(opts, :name, __MODULE__)

download = Keyword.fetch!(opts, :download)

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, download, name: name)

end

@impl GenServer

def init(download) do

schedule(:start, 1_000)

{:ok, download}

end

@impl GenServer

def handle_info(:start, download) do

{:ok, new_download} =

download

|> Download.with_pending_state()

|> Repo.update()

broadcast(new_download)

schedule(:process, 1_000)

{:noreply, new_download}

end

def handle_info(:process, download) do

{:ok, new_download} =

download

|> Download.with_processing_state()

|> Repo.update()

broadcast(new_download)

schedule(:ready, 5_000)

{:noreply, new_download}

end

def handle_info(:ready, %Download{id: id, user_id: user_id} = download) do

{:ok, new_download} =

download

|> Download.with_ready_state()

|> Download.with_file_url("/downloads/#{id}.pdf")

|> Repo.update()

broadcast(new_download)

{:stop, :normal, new_download}

end

defp schedule(action, timeout) do

Process.send_after(self(), action, timeout)

end

defp broadcast(%Download{user_id: user_id} = download) do

PubSub.broadcast(DownloadManager.PubSub, "download:#{user_id}", {:update, download})

end

end

The module is a straightforward GenServer implementation, which takes a name and a download in its options, being download its internal state. It then starts a loop of scheduled internal messages, in which updates its download with the next state, updating the download stored in the repo and broadcasting the new download through Phoenix.PubSub using the download:#{user_id} topic. Eventually, when the download is ready, it sets a fake download URL and exits normally. Let’s jump into iex and test it out:

➜ iex -S mix

Erlang/OTP 24 [erts-12.0.1] [source] [64-bit] [smp:12:12] [ds:12:12:10] [async-threads:1] [jit]

[info] Starting Horde.RegistryImpl with name DownloadManager.HordeRegistry

[info] Starting Horde.DynamicSupervisorImpl with name DownloadManager.HordeSupervisor

Interactive Elixir (1.12.1) - press Ctrl+C to exit (type h() ENTER for help)

iex(1)> download = [user_id: "user-1"] |> DownloadManager.Download.new()

%DownloadManager.Download{

file_url: nil,

id: "QOotjQuQSP",

state: :pending,

user_id: "user-1"

}

iex(2)> DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.Worker.start_link(download: download)

{:ok, #PID<0.379.0>}

iex(3)> [info] ----[nonode@nohost-#PID<0.379.0>] Elixir.DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.Worker.Fake starting download: %DownloadManager.Download{file_url: nil, id: "QOotjQuQSP", state: :pending, user_id: "user-1"}

[info] ----[nonode@nohost-#PID<0.379.0>] Elixir.DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.Worker.Fake processing download: %DownloadManager.Download{file_url: nil, id: "QOotjQuQSP", state: :pending, user_id: "user-1"}

[info] ----[nonode@nohost-#PID<0.379.0>] Elixir.DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.Worker.Fake download ready: %DownloadManager.Download{file_url: "/downloads/QOotjQuQSP.pdf", id: "QOotjQuQSP", state: :ready, user_id: "user-1"}It is working as expected, excellent. We can’t forget about configuring the tracker’s worker adapter though:

# ./config/config.exs

use Mix.Config

# ...

config :download_manager, DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.Worker,

adapter: DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.Worker.Fake

# ...And this is pretty much it in terms of the back-end logic. Therefore, let’s move forward to the front-end and implement the interaction with the user.

Requesting downloads from the UI

User experience-wise, we want to focus on three requirements primarily:

- A user can only request a download at a time.

- If the user refreshes the browser while a download is in progress, the user shouldn’t lose track of the current download once the page loads again.

- The previous point also applies when the instance to which the user connected goes down.

Having this in mind, let’s start by creating a Plug to identify users uniquely, fulfilling the first point:

# ./lib/download_manager_web/plug/auth_plug.ex

defmodule DownloadManagerWeb.AuthPlug do

@behaviour Plug

alias DownloadManager.Token

alias Plug.Conn

@impl Plug

def init(opts), do: opts

@impl Plug

def call(conn, _opts) do

case Conn.get_session(conn) do

%{"user_id" => _} ->

conn

_ ->

Conn.put_session(conn, :user_id, Token.generate())

end

end

end

This plug fakes an authentication mechanism, checking if there is already a user_id in the session, setting a new random one if it does not. This user_id gets stored in a browser cookie, hence every time we visit the application we will use the same user_id. Let’s add the plug into the router:

# ./lib/download_manager_web/router.ex

defmodule DownloadManagerWeb.Router do

use DownloadManagerWeb, :router

pipeline :browser do

# ...

plug DownloadManagerWeb.AuthPlug

end

# ...

end

Having the user_id ready in the session, we can edit the live page module, which is the main and only entry point to our application:

# ../lib/download_manager_web/live/page_live.ex

defmodule DownloadManagerWeb.PageLive do

use DownloadManagerWeb, :live_view

alias Phoenix.PubSub

@impl Phoenix.LiveView

def mount(_params, %{"user_id" => user_id}, socket) do

PubSub.subscribe(DownloadManager.PubSub, "download:#{user_id}")

download =

case DownloadManager.fetch_download(user_id) do

{:ok, download} ->

download

{:error, :not_found} ->

nil

end

{:ok, assign(socket, user_id: user_id, download: download)}

end

# ...

end

In the mount/3 callback, it takes the user_id from the session and immediately subscribes to the down_load:#{user_id} topic. Next, it checks if the user already has a download in progress, assigning it to the socket (or nil if there is no download). Notice that we are using DownloadManager.fetch_download/1 to fetch the download. I like adding all the functions the DownloadManagerWeb.* namespace needs from DownloadManager.* in the main DownloadManager module, acting as a public contract between them, so that the web modules don’t need to know any implementation details of the business modules. Let’s add the functions that we need really quick:

# ./lib/download_manager.ex

defmodule DownloadManager do

defdelegate start_download(user_id), to: DownloadManager.Download.Tracker, as: :start

defdelegate fetch_download(user_id), to: DownloadManager.Download.Repo, as: :fetch

defdelegate delete_download(download), to: DownloadManager.Download.Repo, as: :remove

endAs you can see, it exposes three different functions that delegate to the proper business modules. We can now edit the live view template to add the button which triggers the download request:

# ./lib/download_manager_web/live/page_live.html.leex

<section class="px-6">

# ...

<div class="my-6 flex items-center gap-x-4">

# ...

<%= if is_nil(@download) do %>

<button phx-click="request_download" class="rounded text-purple-200 text-sm bg-purple-900 ml-auto h-8 px-6 flex items-center">Download PDF</button>

<% end %>

</div>

# ...

</section

If there is no download set in the socket assigns, it renders the button which triggers a request_download event on its click event. Let’ implement the corresponding callback in the live page module:

# ../lib/download_manager_web/live/page_live.ex

defmodule DownloadManagerWeb.PageLive do

use DownloadManagerWeb, :live_view

# ...

@impl Phoenix.LiveView

def handle_event("request_download", _, socket) do

case DownloadManager.start_download(socket.assigns.user_id) do

{:ok, download} ->

{:noreply, assign(socket, download: download)}

_ ->

{:noreply, put_flash(socket, :error, "Error creating download request")}

end

end

# ...

end

The function starts by calling the DownloadManager.start_download/1 function which we have previously delegated to DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.start/1, using the current user_id. If the call goes fine, it assigns the resulting download to the socket, setting a flash error if the contrary. By assigning the download, we can show its progress to the user by adding a live component to the page template:

# ./lib/download_manager_web/live/page_live.html.leex

# ...

<%= if @download != nil do %>

<%= live_component DownloadManagerWeb.DownloadLiveComponent, download: @download %>

<% end %># ./lib/download_manager_web/live/components/download_component.ex

defmodule DownloadManagerWeb.DownloadLiveComponent do

use Phoenix.LiveComponent

alias DownloadManager.Download

@pending_state Download.pending_state()

@processing_state Download.processing_state()

@ready_state Download.ready_state()

def render(%{download: %Download{state: state}} = assigns) do

~L"""

<div>

<div class="bg-white p-5 rounded shadow-md absolute top-0 right-0 w-80 mt-6 mr-6 border-gray-100 border text-sm leading-7 flex gap-x-4">

<%= icon(state) %>

<div>

<h4 class="font-bold">Generating downloadable file</h4>

<p class="text-gray-500"><%= state_text(state) %></p>

<%= if Download.ready?(@download) do %>

<a phx-click="delete_download" class="text-purple-800 cursor-pointer hover:underline" hrerf="<%= @download.file_url %>">Click me to download the file</a>

<% end %>

</div>

</div>

</div>

"""

end

defp state_text(@pending_state), do: "Starting download request"

defp state_text(@processing_state), do: "Generating file..."

defp state_text(@ready_state), do: "File generated with success"

defp icon(@ready_state) do

# icon content

end

defp icon(_) do

# icon content

end

endThe download component is pretty straightforward. It renders a popup, changing its content depending on the current state of the assigned download. However, we haven’t yet handled any download progress updates in live view, so let’s fix this:

# ../lib/download_manager_web/live/page_live.ex

defmodule DownloadManagerWeb.PageLive do

use DownloadManagerWeb, :live_view

# ...

@impl Phoenix.LiveView

def handle_info({:update, download}, socket) do

{:noreply, assign(socket, download: download)}

end

end

By doing this, every time the DownloadManager.Download.Tracker.Worker.Fake module broadcasts a download update, the updated download is assigned to the socket, forcing a new render of the component. The last thing we need to implement is the delete_download event triggered from the download component when the user clicks the file URL:

# ../lib/download_manager_web/live/page_live.ex

defmodule DownloadManagerWeb.PageLive do

use DownloadManagerWeb, :live_view

# ...

def handle_event("delete_download", _, socket) do

download = socket.assigns.download

DownloadManager.delete_download(download)

{:noreply, assign(socket, download: nil)}

end

# ...

endThe callback function deletes the current user download from the repository. It also sets the assigned download to nil, conveniently rendering the button again to let the user start a new download request without refreshing the browser.

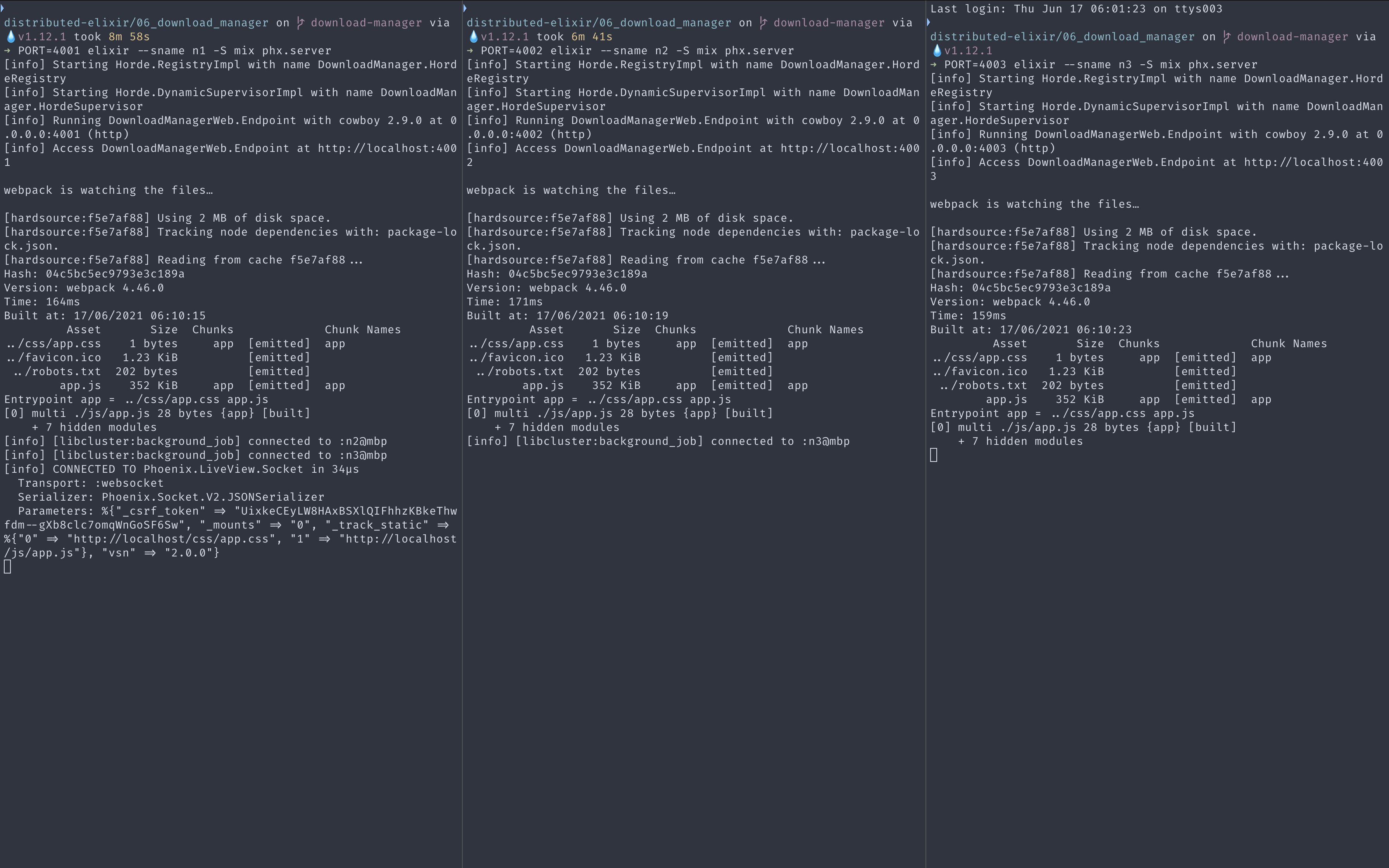

Testing the application locally

Now that we have finished implementing the solution let’s do some local testing. The tricky part of running different simultaneous instances, and let Phoenix do its magic regarding process communication and socket connections, is that:

- We need to run each instance on a different port number.

- We need a single entry point for all the possible nodes.

The first point is straightforward as we have already configured the application to accept a PORT number from the environment. We can start different instances running PORT=4001 elixir --sname n1 -S mix phx.server, using different ports and node names. On the other hand, the second point requires a bit more work, as we need to set up a load balancer. A simple way of doing this is using NGINX with a configuration similar to the following:

# /usr/local/etc/nginx/sites-available/default.conf

upstream loadbalancer {

server 127.0.0.1:4001 weight=1;

server 127.0.0.1:4002 weight=1;

server 127.0.0.1:4003 weight=1;

}

resolver 127.0.0.11;

server {

location / {

proxy_pass http://loadbalancer;

proxy_http_version 1.1;

proxy_set_header Upgrade $http_upgrade;

proxy_set_header Connection "Upgrade";

}

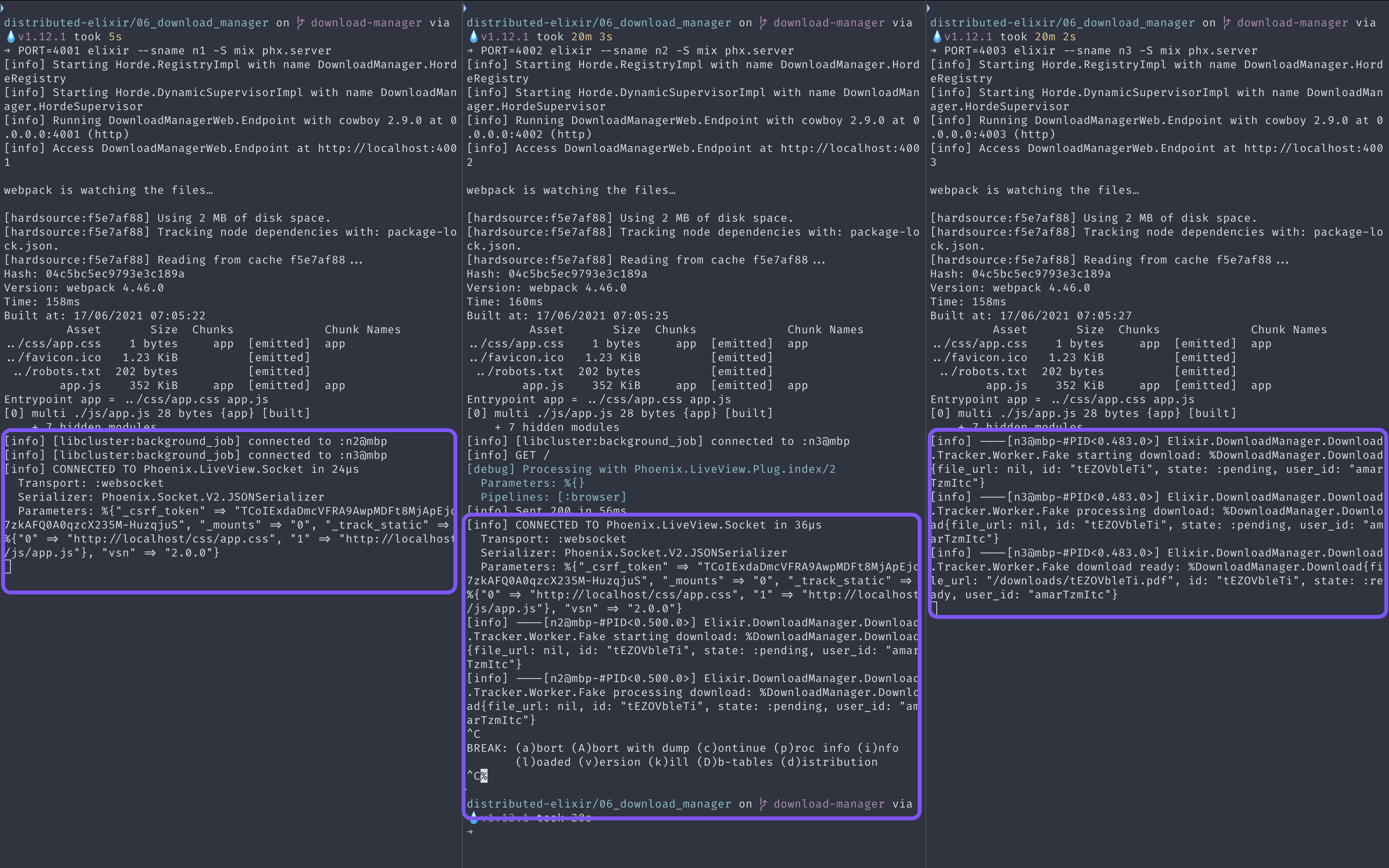

}Once we have the load balancer up and running, let’s start three different nodes on three different terminal windows/panes:

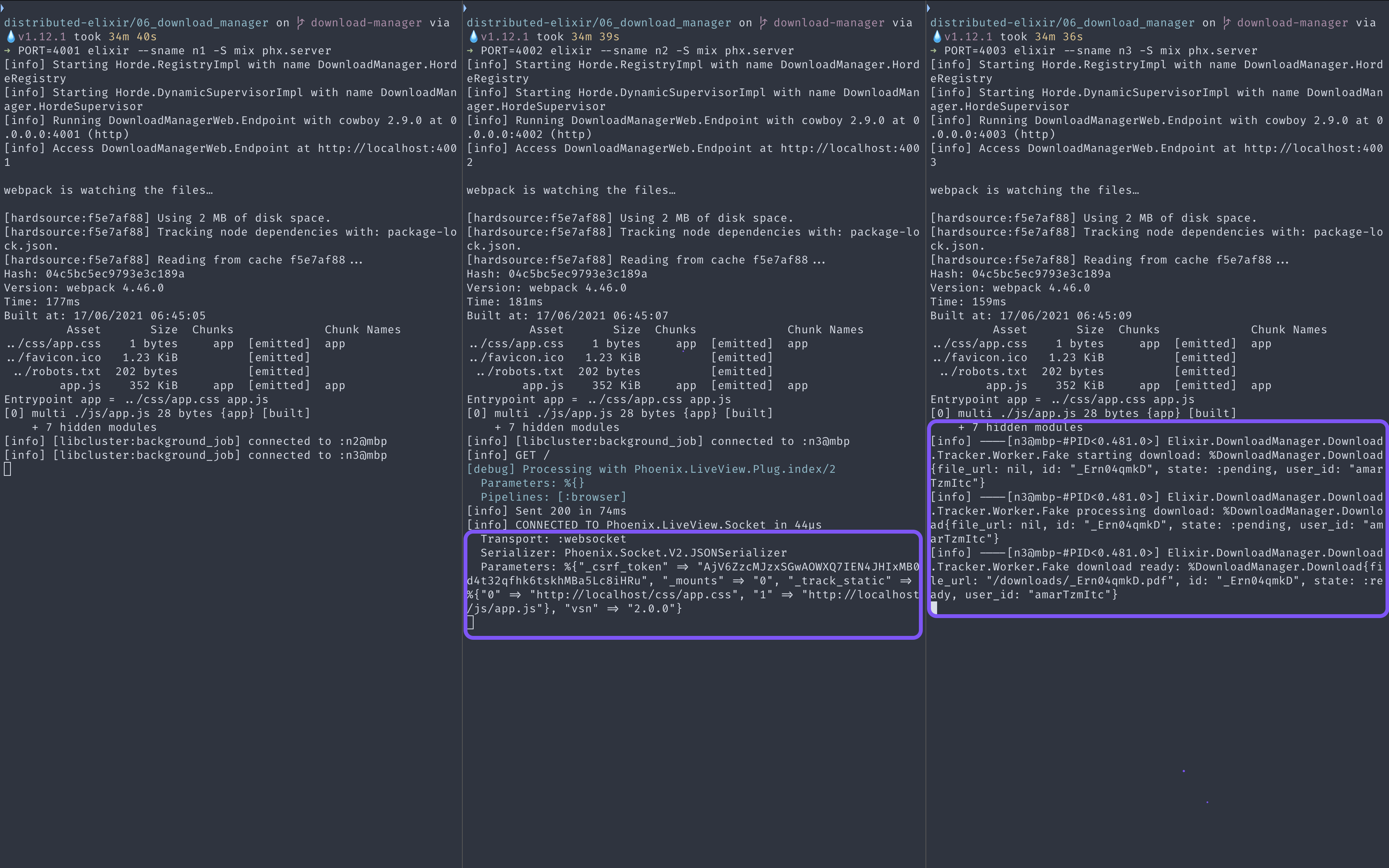

If we jump to the browser and visit http://localhost, we should see our live page. Let’s click the download button and see what happens:

The download message pops up, and we can see the different progress messages until the download is finally ready. Let’s inspect the terminal to see what happens under the hood:

n2 receives the browser connection request, serving the live page. When we clicked the download button, this request started in n2, but the download process spawned in n3 due to Horde’s internals. Once the download is ready, thanks to Elixir’s distribution model and Phoenix’s PubSub, n2 receives the corresponding message, passing the result back to the user through the socket. Let’s start and new download request, and shut down the node where the download process runs:

This time, both the socket connection and the download process start in n2. Shutting down n2 causes the following:

-

The live page reconnects to

n1. -

The download process dies, but thanks to Horde it continues back in

n3. -

n1receives the corresponding message fromn3once the download is ready.

And all of this is totally transparent to the user. Isn’t it amazing?

Conclusion

In this example, we have taken advantage of Elixir’s distributed capabilities to build a practical solution around cross-node process messaging, in-memory storage, and dynamic global supervision. The implementation has been very straightforward and without the need for any external dependency, such as job queues or third-party in-memory storage. In the next part, we will implement the last example of the series: a distributed mechanism that monitors the deployed version of the application in each node, sending a message to the front-end suggesting the user to refresh the browser if a new version gets deployed. In the meantime, don’t forget to take a look at the source code of this example.

Happy coding!